Release Date

November 3rd, 2021

As an Ecuadorian immigrant living in poverty and seeking safety—and later facing rock bottom while confronting substance abuse—poet Diego Perez had a long way to go to find his center. Now, better known by his pen name, Yung Pueblo, Perez discusses his path to personal awakening and a gentler way of being.

“What you end up finding is that not only can you connect with people deeper, not only can you be more present, but you have a new energy for life and you’re able to just allow that sort of raw human creativity to flow much more easily.”

INSPIRATION

YUNG’S TEACHERS

POEMS

TRANSCRIPT

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Redefined is hosted by me, Zainab Salbi, and brought to you by FindCenter, a search engine for your soul. Part library, part temple, FindCenter presents a world of wisdom, organized. Check it out today at www.findcenter.com, and please subscribe to Redefined for free on Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

What’s most important about life? What is the essence of life? Is it what we do, how much we earn, how many social media followers we have? Or is it, do we live our lives in kindness to ourselves and to others? Do we live our lives in love to ourselves and to others? In nearly losing my life, I was confronted with these questions and it led me to the conversations that make up Redefined, about how we draw our inner maps and the pursuit of meaningful personal change.

My guest this time is the poet Yung Pueblo, author of two books, Inward and Clarity & Connection. While I’ve been moved by his poetry, I’ve also been very curious to learn more about the man behind the verse: an immigrant from Ecuador whose given name is Diego Perez. From a young age, Diego has moved through a number of transformative moments. From searching for safety and acceptance in a new country to working as a community organizer from the age of fifteen, to overcoming substance abuse and setting an intention to follow a gentler and quieter path. Sometimes it is the quiet ones who we must take extra care to listen to. I am so very excited to share this conversation with you. Do join me.

All right, Diego, very, very nice meeting you. I feel I’ve been a companion to your heart’s writings and wisdom as I’ve been reading Clarity & Connection. Really in the last month . . . I have a habit of waking up every morning and randomly opening—usually on a Rumi book, and I have replaced Rumi with you, which is a big deal for me because I just love Rumi. And I have to tell you, every time I read one of your poems or praises or prose, it’s calming for the heart. And this podcast, Redefined, is really about redefining moments in our life and what it led us to the wisdom that gets us on a new journey in life. And I read somewhere what perhaps could be a redefining moment in your life or an awakening moment in your life, and correct me if I’m wrong, was when you hit rock bottom and almost died in 2011.

Yung Pueblo:

Mm-hmm. That’s right.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

I got to tell you, I personally resonate with that because two years ago I almost died, and it was a major awakening moment in my life. So I’m very curious, what was that moment like and what was the first awareness that came to you out of that brush with death?

Yung Pueblo:

So it’s interesting because I felt like the moment itself in some ways felt like a surprise, because I was so unconscious of all of my decisions and my movements and how all of that was sort of escalating and snowballing into this one big moment. Now when I look back on it, it seems so obvious that I was heading in this direction, but when I was actually going through it I was like, “What is happening?” It was painful. I think a lot of it was just an eruption of sorrow, because I was really not telling myself the truth about how much sadness I was feeling. And I didn’t want to come to terms with that, and I would use the avenue of pleasure to just run away from myself as much as possible.

But I think what I really came out of that with—literally after laying on the floor and feeling like I was dying, my heart felt like it was just exploding—and what I realized was that I needed to turn everything around. And one of the first insights that came was that my path to well-being had to be through the root of honesty. I needed to be honest with myself, because what got me to that point was just me lying to myself over and over that everything was fine, I didn’t need to deal with all this tension that was in my mind, I didn’t need to address all these unhealthy habits that I had developed over time.

And all of that lying, all of that dishonesty just not only put me so far away from myself, it caused sort of like a cascade of failures in my relationships—with my friends, with my family members—because I was so far away from myself, I was even much more further away from the people that I loved. So it all kind of came to head that night in, I think it was August of 2011, and I felt like, one, I can’t keep doing this anymore. I can’t keep abusing my body in this way by taking all of these different drugs and not knowing where it was going to lead me. And I knew that this was it, because I wanted to live a better life. And I knew that if I really took a strong determination that I could turn things around, and that’s really what happened.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

I’m getting emotional just hearing you. I had abused myself and my body in different ways, more through workaholism, what do you call it? Not workaholic. Yeah, workaholic . . . with a mission—I’m a women’s rights activist and a humanitarian. And so I had a mission—but the mission still drove me to the edge. And so, I’m touched by your experience. And it seems that it puts you on the first step towards the trajectory that led you to become who you are today.

Yung Pueblo:

Yeah, definitely.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

But before we go there, if you don’t mind, I want to go to the beginning, which is, you’re born in Ecuador and your parents and you migrated to Boston. As an immigrant myself, I’m curious about that immigrant story. How old were you? Do you have memories of Ecuador? And how was the journey here? What was the journey here?

Yung Pueblo:

When I look back on my memories, there are very few memories of Ecuador. I think I remember playing outside of our house. We lived in a city called Guayaquil, which is the most populous city in Ecuador. I remember being in sort of the front of the house playing with a toy car. But the memories are very vague, I think it was really when we moved to the United States. I was about four years old. So that was a big transition from being a small, infant child to being a young kid. And when we got here, I think it was tough. It was tough being totally removed from all of my aunts and my uncles and my cousins, and it just became our immediate family unit, that we had to survive ourselves. And it was difficult. It was a pretty typical American immigrant experience. We came here and my parents just had to work so hard.

And I think it was . . . you know, growing up a lot of my patterns of anxiety and sadness revolved around this struggle with poverty, because poverty creates so much insecurity, and I would see the way that it would push my parents to the edge. My parents were really good people, but then if you’re living amidst the . . . sort of like the struggle, this river of poverty, it will cause the sort of rough aspects of yourself to become rougher, because you’re trying to survive. It almost feels like you’re drowning all the time. They were always trying to figure out how to pay rent, they were always trying to make ends meet, and it was tough watching them go through that. And it’s quite interesting now seeing the difference where my parents love each other so much, but because there was so much external pressure on them they would fight all the time when I was growing up, because they didn’t have anyone else to share their tension with, and a lot of this tension was material.

Now, when my brother and myself and my sister, we’re adults, we’re growing up and we can support our parents better . . . They themselves are still working, but they don’t have that same intense lack that they used to have when we were younger. They love each other so much, there’s so much harmony between the two of them, and you can really see that their marital issues were actually driven by a lack of money. And it’s a very real thing that we went through. But it was hard, you grow up in America, you experience a lot of racism, you experience a lot of just being other-ized. You don’t see yourself on TV. You kind of grow up living in multiple worlds at once. You’re Ecuadorian in your household, you speak Spanish in a very particular way in your household, but then when you go outside, and you’re in school, and your friends, you’re speaking English and you’re speaking different types of Spanish, and you’re just living multiple identities at once.

And it was tough and beautiful at the same time. I think it was incredibly formative, but it’s something that I have a lot of compassion for the people—even family members who are coming into the country now—it’s tough. It’s a tough road to be able to transition from what you grew up in and what you know in the hope of a better life, right? There’s no certainty to it, and in a lot of ways it’s a bit of a gamble, because I’ve known a lot of people who grew up and moved to the United States at the same time as me who did not have as good stories and really ended up struggling in the long run.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Thank you for bringing that, because then it humanizes the experiences of what it means to be angry. Humanity is the experience of the other, because it’s so easy to point the finger and say, “Look at these other people from other cultures, from other class,” whatever. “Look at them, how they’re doing that.” Well, they don’t have the circumstances that sort of gives us the peace of mind every day.

Yung Pueblo:

It’s really true. And there’s two things that come to mind. One is that you can’t pull someone out of their context, right? So you see someone in one instance, and they’re doing one thing, but you have to think about all the cause and effects that had to come together for them to have that explosion or say the meanful thing, or what was it that was triggering them to get to this point? And on the other side of that, being an immigrant in the United States is that there are definitely some success stories, but outside of those success stories there are very many stories that do not go right, that are never highlighted, never talked about, because you don’t quite understand how many things have to go right for you to be able to be a success in this country, especially a country that wasn’t initially very inviting to you in the first place.

And I think a lot about that for myself and my own personal history, and then I think about the people that I went to elementary school with or middle school or high school with who are still trapped in the poverty trap. They’re still in the poverty trap. And I was fortunate that things went right for me, but at the same time, in no way do I think like, “Oh, I’m special.” A lot of times it feels like you won a lottery and you’re fortunate, but it’s a tough road. It’s a tough road being an immigrant.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Was that part of the unsafety that you felt and you talk about?

Yung Pueblo:

Yeah. Yeah.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Can you talk more about that? I mean, was it caused by . . . Again, as an immigrant, I know what the kids go through, and the labeling, and the joking and the ridiculing and, and, and, and, and, right? From their accent to their food to their color of their skin, et cetera. What were these experiences for you and how have they scarred you, if they did?

Yung Pueblo:

Yeah. I think a lot of the toughness, too; it’s this symbiotic relationship that we have with our parents. So, my dad, he worked in a supermarket and my mom worked cleaning houses. So they were really just making very low wages. So we were never able to, especially as kids, we weren’t wearing the nice clothes that were cool, we didn’t have the right shoes, because we were always struggling to make ends meet for our most basic . . . food, and our rent. We ended up standing out, because we didn’t have Jordans or we didn’t have these types of clothes and whatnot when my brother and I were growing up. But the scarring aspects were the internal things, especially when I started becoming older and I was thirteen and fourteen, and I started seeing the relationship of the difficulty that my parents were having that was directly tied to money.

And I started asking myself, like, “Why are things like this? The world does look rather abundant, but why do some people have to suffer so much, especially with these basic material things that should be widely available.” And I think a lot of those things sort of pushed me early on to just go into the world of activism. So I was an organizer, very young, in Boston, from the ages of like fifteen to . . . I took a little break when I was in college and then I came back and kept doing similar work when I was up until twenty-four, but I got to really start learning and acting on the fact that we can make society better, and that we can actually make changes in our material reality if we started working in cohorts and collectives and started gathering our power to then sort of push people who had power over us to literally give us the things that we want, like changing laws in the city or changing the way our schools were structured.

And literally being able to activate our power like that, I think, was something that was really healing. But yeah, when I think about what scarred me the most, it was my experience of poverty, of just not having, and that just kind of rippled out into having these patterns of insecurity, patterns of anxiety, patterns of not having enough, patterns of really just fear-dominated.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Often those who go into activism, and I’m speaking about myself, and it took me a very long time to realize, “Oh, my gosh, my activism is directly related to my trauma.”

Yung Pueblo:

Yep.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

And for me, I was chanting for women to speak their truth, break their silence, be independent. And honestly, I was thirty-five when I realized, “Oh, I am really talking to myself. I am asking others to do what I really want to do in myself.” And rather than going inward and addressing it, I sort of expressed it outward. So it seems that there is [a] similar journey, except you have done it in a much earlier age, fifteen to early twenties. At what point did you realize your activism is an extension of your trauma—if it is—and that, “Oh, I’m expressing it externally, but I really need to work on it internally”?

Yung Pueblo:

Oh, that’s a great question. I think a lot of that realization came after. When I was twenty-four I ended up taking a big step back. I wanted to just spend a lot more time going to meditation courses. I switched cities. I went from living in Boston to living in New York City. But I wanted to spend time alone, and I wanted to not keep doing the things that were familiar to me so that I would really just get to know myself, because that was sort of the real beginning of my healing journey was when I was twenty-four, but it got really serious when I was twenty-five and twenty-six. And I think in that period, and when I was looking at my life in retrospect and I could see how important activism was for me, and being in these organizing circles that I was a part of . . . at the same time I knew that I was wholly unprepared for them.

I wanted to be able to share power, to work in sort of circular manners that weren’t just pyramidical, where it’s one person’s in charge. I was sort of pushing myself to grow in these ways. And I didn’t have role models of how these things should be, because all of our society . . . And I’m talking about pyramids, right? So all of our society is shaped in pyramids, where power and money go upward. And there’s very few people who control things and have a lot of decision-making power. And we’re sort of ingrained in these ways through our culture and our society, and then we will actually absentmindedly take these similar models into our organizing work, and we don’t actually know how to function in a circle where everybody has power, and we can come up creatively together with these solutions.

So I would see the way that fear, right?—going back to my traumas of fear and anxiety—they support that idea of the pyramid of like, “Okay, someone has control, so let me try to get as far up there as possible so that I have as much power and I can control the situation.” But as an activist and as an organizer, I was trying to teach myself like, “Okay, how can I let go so that everyone around me, including myself, we’re happily working together and making decisions together so that no few people have too much power over others?” And it’s hard. It’s hard to be able to model the world that you hope exists in the future. But yeah, a lot of that I realized later on.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

It’s very impressive. I mean, it reminds me of Che Guevara who said revolutionary leaders overthrow oppressive leaders only to become the oppressive leaders themselves.

Yung Pueblo:

Absolutely. Absolutely. If—

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Go ahead. No, because it says about relationship with power. And if the relationship with power doesn’t change then we will replicate what we’re trying to change to start with.

Yung Pueblo:

Exactly. Exactly. And I think that’s one of the things that pushed me to step out of the organizing circles that I was a part of, because I felt like I needed to spend time dealing with the roots of craving and aversion and ignorance in my own mind if I were to one day go back and continue doing work like this, because it’s so easy. That quote of Che Guevara is absolutely apt. And you think about other people like Mao or Stalin. You just go through history and it’s like what happens when you give an individual an immense amount of power? Their ego explodes, right? The roughest parts of your ego even if you have beautiful values.

You can have beautiful values, but then you gain power, your movement that you’ve been leading becomes so successful that you start winning, but you never dealt with the roots of your mind, you never dealt with the trauma that was so deeply embedded in there that it actually forces you to recreate all of these old things that you actually were fighting against in the beginning. And you find that time and time again throughout history. There are so many different historical examples of people who try to change the world, but they just do not know how to change themselves, and then they ended up recreating another form of harm.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

That’s so true. It is so true. Are you worried about activist today? I’m thinking of one of your prose. And it’s odd to read your work for you, but it’s really . . . I mean, you can see my book is full of marks. It says, “When you dislike what someone has done and you are quietly rolling in animosity towards them, you are not only weighing yourself down, you are strengthening future reactions of anger. Progress is realizing that fixating on what happened cannot change the past, but a calm mind can certainly help your future.” I actually don’t know if you were writing it about activism or about yourself, and it can apply, I think, to all kinds of examples. But are you worried about the activism of today? Because we are in a polarized society and there’s so little going on in terms of reflection on ourselves and engaging with the other in a different way, and frankly, regardless of which side of the aisle one is. Are you worried or not?

Yung Pueblo:

Yeah. I think I have a lot of hope and there are definitely concerns. I think my concern is around the word justice. I think it’s very easy to confuse justice and think about it as another form of revenge. Revenge doesn’t fix anything, it just actually continues the cycle of harm. Justice, it needs to be something that is really imbued with love. I think I feel it was Thich Nhat Hanh or somebody said, and I saw this posted somewhere the other day, but justice needs to be embodied with understanding and love so that, yes, we are able to correct errors that have occurred as best as we can, but we’re also not going to go crucifying people left and right, because they made mistakes or even if the mistakes weren’t mistakes and they were intentional, because one thing you can go back to the old sort of tribal mentality, right? And where, “Okay, you hurt my family, so my family will wait for the right time to come and hurt you,” and then we’ll be falling into these cycles of retribution over and over again. But then what happens? Is just a bunch of people getting hurt.

So if we really want to stop the situation it needs to become led by love in a way where we can start something new, start something fresh and we can be like, “Okay, these harms have occurred, but now let’s move forward in a way that’s productive for all of the parties involved.” And we can move forward with our lives without having to replay the past over and over, or without having to wait for another moment to strike at each other again. Because if you think about the actual, right? And you bring in the teachings of the Buddha into the situation: if you’re trying to seek revenge on another person the first person that’s going to get hurt is you, because the intensity that has to occur in your own mind for you to try to punch someone, or stab someone, or shoot someone, you have to create so much tension, so much aversion to then commit that action.

You’ve already have scarred your own mind, even before you even take that action. And then when you actually go through that action, then it becomes even deeper, and then you have the potential retribution of karma that may be coming your way. So, revenge does not serve you, because you’re literally just weighing yourself down.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

One of your pieces in Clarity & Connection reminds me of that, because in it you say, “When trauma becomes a part of your identity it is harder to heal. The narratives that define how you see yourself need space to change. Acknowledging your past is important, but so is doing the work to unbind those old patterns so you can move beyond them. Allowing your sense of self to be fluid will support your happiness. Change is always happening, especially within you.” It’s hard for people to let go of the trauma, because in my experience the trauma can become such a core point of identity. So it’s almost like if you let it go, then who am I?

Yung Pueblo:

Who am I? Yeah. Yeah.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

So how did you do it? How did you do it?

Yung Pueblo:

Yeah. A lot of the things that I write about in my book . . . they’re points of reflection and they’re ideals to strive for. I know it’s hard. It’s hard. It’s not meant to be—especially the inner work—it’s not meant to be easy. But there was something that struck me, when I started meditating with Vipassana, and I started being able to feel, really literally feel, how much change was happening in the body and how rapidly things would be changing, much more than I can count, there’s just waves and waves of oceans of atoms, right? Happening at just incredible speeds. And it’s very easy to be unconscious of these movements happening in the body. But it started dawning on me that I would conceive of myself in a very static way in the past, that my identity was this and that it was always going to be this.

But in reality, when I was able to observe what’s true, is that my identity is a river, right? It’s a river. It’s moving, it’s changing, it’s bobbing, it’s weaving. It’s moving at different speeds, it’s slowing down or going faster, and it spreads and widens. It really hit me that a lot of this tension that we have is when we sort of freeze the idea of the self and you don’t give it any flexibility, flexibility to allow some parts to just kind of let go with, because they’re no longer part of you, or to add on new parts, even though that might be scary, because you’re growing and you’re changing. And I vividly remember as a child hearing people take pride in the words, “I never change. I’m always the same, I never change.” And I remember hearing that a lot.

And when I started meditating, I was like, that’s tough, because if you actively try not to change that means you are trying to flow against the natural river of change. You’re literally flowing against the universe. And that’s going to hurt, because all this universe is, is change. And being able to adopt that change and allow yourself to just become what you are in the moment, because especially as we grow older, especially as we start actively healing ourselves, there are parts of our identities that no longer fit quite right, right? That they just feel like an old shirt that just doesn’t fit right and you need a little more room or it needs to be a little more stretchy. And I think personally allowing myself that type of flexibility has been just a gift, a gift that I’ve been able to openly receive, because I’m so much more than who I was, and who I am now will continue to change. And I think living in alignment with that has helped.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

I once went to a silent meditation. Honestly, it was right after Trump won and there was the Muslim ban. I’m a Muslim and I was scared and confused. You immigrate to this country to find safety and then you don’t find safety here, and it was like, “Where do I go?” So I went to silent meditation for four days. And the first day it was all anxiety and looking at all my issues. And the second day I’m deepening the looking, and I’m afraid, “I’ve failed, oh my God, I’m unsafe,” all of that. And the third day, I call it what it is. I call all the emotions what they were, rather. And the fourth day, and this is where you remind me of what you’re saying, my soul—I call it my soul, not my identity even—my soul, it was freed from all these labels, right?

And I just remember seeing my soul dancing in the room without any boundaries. There were no walls, there were no identities even, it was just a free soul. And I think that’s what you’re talking about, it’s when we look into the issue and dig deeper, once you name it and you call it, you actually can free yourself from all of these things. But it’s courageous and it’s hard, right? And you talk about it being hard, and a lot of people don’t want to do that. You didn’t also want to do that. I mean, you talk about—

Yung Pueblo:

Yeah.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Right. So, when you go through this cornered, anxious moment, what do you do to like, “Okay, no more distraction”? I think you don’t even drink coffee, actually. I don’t know, I heard you barely drink . . . What do you do where you’re like, “I’m staying here. I’m not leaving”?

Yung Pueblo:

I think what I do to keep myself going, I really try to hunker down on my strong determination. But the only reason it works is because I remind myself of what I gained from this in the past. Right? I remember I did my first silent ten-day meditation course. It was wildly difficult, immensely difficult, the hardest thing I’ve ever done. But then afterwards, I knew that I felt better than I’d ever felt before in my life. My mind felt more free, I felt like I could connect with people more deeply, and that my mind wasn’t reacting at the same intensity as it was before. So when I saw those results, I was like, “Man, that was hard, but I got to go back.” I got to go do this again to see if I can keep working on these issues, and see if I can keep moving in a direction of more equanimity, that word meaning being able to really observe things without craving, or aversion to observe them with a balanced mind.

And I’ve gone to many retreats since then. I started back in 2012. And it’s always hard, but I keep going because I know what it’s given me before in the past. And it doesn’t mean that the results are always the same. Sometimes I come out and I get very unexpected gifts, because I’m not aiming for more bliss or anything like that, I’m aiming for more of an ability to just observe reality as it is, whether it’s hard or easy. And yeah, I think that’s been my main tactic, is like, “Okay, this is extremely difficult, but it has given you so much. So trust the process in this moment, even though it’s hard.”

Zainab Salbi (Host):

So, my summary of it is that the taste of freedom is so delicious, that it makes the hard process worth it.

Yung Pueblo:

Yes. Yes. That’s very apt. Yeah.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Let’s talk about your career, because I heard that you wanted to go to finance to make money and then you ended up being a poet, which a lot of parents would be worried about, at least in my culture, they’re like, “No, no, no, don’t be an artist here. You’re not going to make money.” And here you are, not any poet, a thriving poet with a lot of people, and not only celebrating your work, but also impacted by your work.

Yung Pueblo:

I never knew that I was going to be a writer. I think to this day, it still kind of surprises me that this is what I do, because I love to learn. I learned so much when I was at university, but when I got to the actual meditation courses I felt like I was learning so much more and so much faster. But through that process of purification, right? Where you’re literally unbinding the mental patterns that have been so deeply conditioned over time by all of your reactions, a new ability, a raw creativity emerges. And this isn’t just for me, right? It’s for anyone who does this deep internal work. What you end up finding is that not only can you connect with people deeper, not only can you be more present, but you have a new energy for life and you’re able to just allow that sort of raw human creativity to flow much more easily. And when I came out of these courses and I started writing a little poem here and there I was surprised, I was like, “Wow, I’ve never done that.”

And as I kept going I started getting a very clear message from my intuition, that it was like, “Drop all the other plans, just focus on writing. You’re not fully healed, you’re not fully wise, you’re still on your path, you’re still walking. But it’s important to support other people in their healing, even if they’re in different modalities, whether you’re seeing a therapist, whether you’re meditating, whether you’re journaling. As long as you’re trying to be introspective in some manner in a way that helps you emerge as a better person for yourself and for other people then that’s huge, that’s something that I should actively be trying to support.”

And to me, it kind of clicked, because it was engaging people from a different direction, sort of in a similar way where organizing and healing, they have to go hand in hand, right? We need to be able to create a better world, but that better world is going to stand on our ability to love ourselves and love each other really well. And that felt important. I remember I talked to my wife about that, because we had recently moved to New York City and were planning on getting . . . I’m working and figuring out our lives, because we were still very young at the time. I asked her if she would give me time, give me time to be able to figure myself out as a writer, and she said yes. And I was very fortunate that she gave me that time to just focus and see if this was even a possibility, and then over time we did see that if I keep going and I keep sharing and trying to be honest and authentic that people may connect with this message.

And I always knew in the back of my mind if I’m able to create material that people find useful and I put it into a book format then it might sell. And I don’t know how much it’ll sell, right? I have no idea, but if it does and then money will come in some way or another. And that’s kind of how it went. I didn’t really go into it for the money, but it felt so clear in my intuition that it was just like, “Okay, this is a very unknown world for you, you’d never wanted to be a writer, but do this.” It felt like it was coming out like a fountain, it’s just clear, and it was a great—mostly due to my wife. She was the one who gave me the support and without her Yung Pueblo would never exist.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Well, let’s talk about Yung Pueblo. I’m curious about the change of your name. Now, I have read about why you changed your name. I mean, rather what is the name mean, Yung and Pueblo? But why is what I’m interested in. Why is it not Diego who is out there in the world? And again, there’s a Talmudic saying that “we see things as we are, we do not see things as they are.” So a lot of times when I ask you things I could be also projecting. As a Muslim and as an immigrant a lot of friends changed their names out of fear, because they didn’t want to be called a name that would show their foreignness. And that’s one reason a lot of people feel, “No, my identity is different. I am no longer this, thus I am this.” I’m curious about the process of the decision-making that you said, “I am going to have another name.”

Yung Pueblo:

Yeah, yeah. I haven’t thought about this in a while, but the current that we’re currently on, the two of us talking in this conversation, it’s reminding me that I picked the name Yung Pueblo, because “Yung” coming from the United States. That was sort of me locking my two sort of major parts of my identity together, my Americaness and my Ecuadorianess. Because “Pueblo,” I mean, it’s a word that’s used super widely, but it’s very much so used in my country in Ecuador. And then it refers to the masses of impoverished people. And Yung it was just stylistic, I dropped the O, but pretty quickly it became clear to me that humanity as a whole is very, very young. We think we’re mature, we think we’re very advanced technologically, but in terms of our morality, in terms of our love, in terms of our compassion for each other, for ourselves, we’re very in these very early stages, because we have not yet figured out how to live well without harming each other.

I think in terms of how really advanced we are, we’ll know we’re there when we’re able to do those sorts of basic things that our first teachers tried to teach us when we were small children. How to clean up after ourselves, how to not hit each other, how to tell the truth, how to be kind to one another, these basic things that you learn in kindergarten. Some of us may be able to do these things as individuals, but as adults, as a human collective, we don’t know how to do these things at all. So to me, it just felt important to be able to put my work within this framework, that humanity is maturing because it would guide my work. Even though I write a lot about relationships or I write a lot about the individual, these are all sort of the foundations of society as a whole. How we treat each other in our intimate relationships, how we treat each other as friends, as family members, from there emanates our society. So it’s important to be able to realize the importance of those moments that we have with each other.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

You mention your wife a lot. She’s also [a] very integral part of the book. I mean, I feel her at least, because you talk about relationships and of course, you talk about other relationships. And you talk about relationships where you are not a good friend and you are not a good boyfriend. And tell me about the process of ultimately how you nurture, rather how were you, in radical honesty, to quote you, to yourself about your role in relationships? And what do you do now to catch yourself? And as you even evolve with your wife together, what do you do now to sort of move forward together and separate? As you also mentioned, I think in your book.

Yung Pueblo:

I mean, especially with the radical honesty that I express to myself, I’m always trying to be very clear and own the friction that I’m bringing to any situation. So if I’m feeling tense, throughout my day I try to pay a lot of attention to my own mental movements. How does my mind feel right now? Because then I can see and hopefully stop any sort of wild story building that may occur in the mind that may try to place my inner tension and somehow try to make it her fault or my brother’s fault or someone else’s fault, when in reality, no, it’s just when . . . As soon as aversion starts fueling itself, right? And there’s a lot of this tension occurring in the mind, it will start bending logic to be able to give itself even more ammunition, to give itself more fuel. And this is something that every person’s mind does, but when you bring self-awareness into the process that’s how you reclaim your power so that you don’t fall into the trap of this silly storytelling that actually isn’t fully based in reality.

That’s one thing that I’m always trying to do, especially between my wife and I, I’m just like, “Okay, if I don’t feel well I just let her know,” like, “Hey, I don’t feel well. I feel pretty rough today.” And that helps her know that if I’m not up to a particular standard, or say something silly, she’s like, “Oh, right, right. He doesn’t feel good.” And she does the same thing with me too. She’s constantly letting me know. So not only are we communicating about the ways that we should try to support each other in that day, or what’s really important for us to accomplish in that day as individuals, we’re also constantly communicating with each other about where we are in our own emotional spectrum.

If she tells me or she just wakes up and she just feels angry for no reason, that’s fine, it’s like then that gives me the information that I need to be gentle with her that day and to not ask too much of her. We were both very serious about our individual healing processes, so that means that sometimes, especially when you’re healing gets a little bumpy, you’ll need a lot of your energy to be internal and to be focused on yourself so that you can process the things you need to process, and you can get over the humps that you need to get over to be able to feel freer. But a lot of times that’s a day-to-day process, right? One day will feel good and another day won’t feel quite as good, but being able to know where each other stands and not expecting each other to constantly be happy a hundred percent of the time—that has made a world of a difference.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

That’s beautiful. I mean, you’re taking radical honesty into oneself, into communication with each other, and constantly taking that responsibility for not projecting on the other.

Yung Pueblo:

Exactly. Exactly.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Yeah. Yeah. That’s beautiful, truly beautiful. And it takes discipline and safety to keep that space going. What is your relationship with God? Because you talk about meditation and the Divine . . . And meditation, for me, it brings me to the divine. But you grew up, I’m assuming, Christian, and I’m just curious, what is your relationship with God or the Divine? Or how do you experience that or define that, if you may, actually?

Yung Pueblo:

Yeah, definitely. Yeah, I grew up Catholic, and I grew up very Catholic, and was even an altar server, and my family—we were really immersed in the community. But I think what I’ve been learning . . . When I think about God, I think about it as truth, and I think about it as a truth that my mental impurities get in the way of fully being able to grasp. So what I try to do is that I use the Buddhist method for mental purification for me to be able to more deeply immerse myself in truth.

And I can’t say what this is or what it is not until my mind is fully purified. So I’m patient. I keep meditating and I keep trying to immerse myself in truth as much as possible, and then one day it’ll click and I’ll understand what is what. That’s the way I sort of live my life. So I try to be very gentle with my views, and I know that to be able to fully immerse myself in truth I actually have to surrender all of my views, all of them. And that’s really how I try to meditate, let me just see what is real.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

I’m crying as you can see. I mean, you have a magical way of touching people’s souls deeply. It’s truly beautiful to witness you, and I’m so deeply touched to be in conversation with you. So, thank you very, very, very much. And before we go, I have quick questions for you. What books that have stayed with you and truly impacted who you are, stayed in your DNA, if you may?

Yung Pueblo:

There’s two in particular. There’s Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse—that one rocked my world. I think that’s the book that I’ve read the most in my life. I think I’ve read it about four or five times. There’s something about the way that he’s able to express words in such a lyrical manner. So not only in terms of the story, but in terms of the beauty of the writing and its simplicity. He has that quality of minimalism I find so precious. And I’m always trying to bring minimalism into what I’m saying, because I think too many words can skew the message. So that one’s been really important.

And on the more technical side, there was this book that I read called In the Buddha’s Words by a monk named Bhikkhu Bodhi, where he took actual scriptures of the Buddha and sort of highlighted what the Buddha actually said, because oftentimes people talk about what the Buddha said, but they’re like—it’s not quite accurate. So this book in particular I found just absolutely fascinating and really inspiring. Similarly, there’s another one called The Buddha’s Disciples, who are not that widely known of, but just such spectacular lives that are so inspiring where you’ll see people’s . . . their struggles and their suffering and then you hear the story of how they come out of suffering, and all of it is wildly inspiring. Those three books really kind of stand out for me.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

That’s beautiful. Movies that uplift you or you always go to for solace or inspiration?

Yung Pueblo:

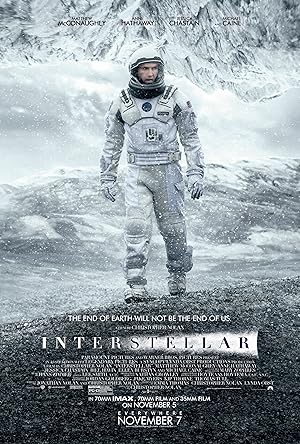

The one that really gets me every time is Interstellar. That movie I find just stunning. I think it’s visually stunning. The story . . . Yeah, the interdimensional part aspect of it—I thought it was just phenomenal. And I think I watch it once every year and I always find it just immensely moving, and I end up creating art right afterwards.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Beautiful. Beautiful. How about teachers? Teachers as in philosophers, or about mentors, or however you define teachers that really shaped you.

Yung Pueblo:

Yeah. The teacher that sort of stands in my mind above is this person that a lot of people don’t know about, his name is Sayagyi U Ba Khin. His real name is U Ba Khin, and Sayagyi meaning, I think it’s “respected teacher.” He was a teacher of S. N. Goenka, and S. N. Goenka is the person that we learn meditation from in the meditation tradition that I’m a part of, but his teacher, Goenka’s teacher, U Ba Khin, oh my goodness, this person, his grasp of truth is just unparalleled, his ability to be able to really understand the nature of reality and to be able to teach people how to be able to walk the path themselves. I take everything that U Ba Khin says very seriously. It’s tough that I haven’t overlapped with him in this life. I think he died in 1970 and I was born in ’87, but this person I really look up to immensely and as a teacher.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Beautiful poems that you often go to or poets?

Yung Pueblo:

That’s a good question. It’s funny, because I’m a poet, but I don’t read a lot of poetry. I mean, the works of Hafiz and Rumi really stand out for me. I mean, there are some poems that really shook me to my core. I think the one that really stands out is the one about the relationship with the sun and the way the sun gives us light, but it’s a gift that’s been given to us and that we don’t have to pay anything in return. I think that poem, and totally botching it, but it shows me the nature of unconditional love and that selfless quality of really being able to love someone well and being able to just give. I’m going to give this to you not because I want you to do something, I’m going to give it to you because I want you to shine. That’s all I want from you.

And the other one that stands out a lot in my mind is by Lao Tzu, the one about trying to change the world and what he realized the best thing that he could do is awaken himself. And I find that lesson over and over again, because we get so excited when we actually find a path of healing that works for us. And there are so many different paths, right? People can find healing in a lot of different ways, but we get so excited and we want everybody to do it our way or try this, but ultimately, all you can do is model the change that has happened within you and live it authentically without showing off or anything like that, but you just live your life, and that shine that is emerging from within you, the right people will gravitate towards it, the people who will resonate with a similar sort of technique that you do, and you let them know what it is that you do and then they’ll be able to benefit from it as well.

But I think it’s important, because we live in a time of such abundant modalities. There are so many different modalities and it’s beautiful . . . That we should support each other in doing whatever it is that we need to do to heal ourselves. Because what I do, and what my best friends do, or what my family members may do it’s very different.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

Thank you. What a pleasure. Thank you, Diego.

Yung Pueblo:

Thank you too. And I have to say this, this has been just such a moving, stunning conversation. I’m deeply, deeply grateful. And thank you for bringing the immigrant aspect and really shining light on that, because something I don’t quite get to talk about as much, but it’s critical to the river that I am right now.

Zainab Salbi (Host):

That was Diego Perez, also known as Yung Pueblo. His books, Inward and Clarity & Connection, are available now from your favorite bookseller. For transcripts and other resources from this episode, please go to www.findcenter.com/redefined. You can follow Diego on Instagram @yung_pueblo. Follow FindCenter on Instagram @find_center. Follow me @zainabsalbi. And please do email me questions about this podcast and your own transformative moments at redefined@findcenter.com. Thank you so much for listening, we’ll be back next week for another conversation about life’s turning points and lessons learned. My guest will be author and human rights advocate Elif Shafak. Redefined is produced by me, Zainab Salbi, along with Rob Corso, Casey Kahn, and Howie Kahn at FreeTime Media. Our music is by John Palmer. Special thanks to Kathy Hilliard, Neal Goldman, Jenn Tardif, Elijah Townsend, Amanda Graber, Caroline Pincus, and Sherra Johnston. Looking forward to seeing you next time.